It’s not everyday that you find yourself in a tiny boat on the Danube, squashed by the borders of Serbia and Croatia, with five libertarians, a future diplomat to Liechtenstein, and a self-proclaimed cannabis shaman, on your way to the newest (self-proclaimed) country in the world: Liberland.

It was just one kilometre upstream. An easy trip, right?

Wrong…

The story of Liberland began in 2015, when Czech politician Vit Jedlička walked onto an abandoned piece of swampland on the shores of the Danube. Believing that a seven-square-kilometre piece of swampland there was terra nullius, available under international law, he places a yellow flag into it and declares himself president of the Free Republic of Liberland.

My first email to the Presidential Office of the Free Republic of Liberland was about a year later. On a wet Wednesday evening, I received the following reply:

“Dear Adam, I am thinking about going for lunch with you on Tuesday. What do you think? Where do you suggest to go?”

President Vit himself. Not only was I in contact with a head of state, he wanted me to suggest where we could meet for lunch! I mostly eat at döner kebab stalls inside subway stations. These places are not presidential. I suggested a Russian-themed restaurant in Berlin Mitte called Gorki Park, finding the irony of taking a libertarian who despised government and taxation to a restaurant celebrating Soviet socialism just too good of a chance to miss.

Below murals of Russian peasants carrying apples and Sputnik memorabilia, I found three men in suits waiting for me. I looked down at my creased blue shirt and dirty black jeans—I wasn’t. I was dressed as if I’d just finished fixing some troublesome bathroom plumbing. To further undermine my credentials as a “journalist,” which was what I was pretending to be, I’d also forgotten my wallet. While extremely embarrassing, this at least saved me from the inevitability of opening it to discover it had no money inside.

I found Mr President at a corner table, perusing the menu. He was heavyset, had a squishy, warm face, cheeks like pockets, and a neat blond goatee. His entourage moved to another table so we could talk privately. I began the interview by accidentally insulting him, when I Liberland a micronation.

“We’ve got four hundred thousand people applying for citizenship.” He tilted his head. “If we accept them all, we’ll be larger than Iceland. So are we still a micronation?”

We’d not even ordered drinks yet, drinks I couldn’t actually pay for, and yet I’d already questioned the man’s sovereignty. I tried to soften my approach. Not that he was being defensive or aggressive. He was calm, friendly, charismatic. I liked him.

I leaned forward. “Well, obviously you know this better than me. To me, it looks like there is a border dispute. Serbia is saying ‘It’s not ours’ and Croatia is saying ‘We’re not sure whose it is, but it’s certainly not yours.’”

He frowned. “Croatia says it’s theirs. But then if it was, why would they stop us going there? Since we wouldn’t have to leave Croatia to do so?”

I wasn’t prepared enough to answer. I wasn’t prepared at all. I thought I was just meeting some crazy opportunist who wanted to get some press for himself, sell some T-shirts, and be able to travel the world introducing himself as Mr President. The intensity of his gaze and the size and professionalism of his entourage convinced me that this wasn’t the case: they were serious.

Vit isn’t just some Internet chancer; he knew his way around politics. He’d been an elected official in his native Czech Republic, but had grown disillusioned with public office there when a former KGB agent was democratically elected as the Czech finance minister. “People vote into power the people who steal the most from them through taxation,” he lamented.

“But he was democratically elected, right?”

He scoffed. “Hitler was also democratically elected. There is no virtue in democracy.”

I’d always assumed democracy was, as Winston Churchill had once quipped, “the worst form of government, except for all other others.” People went to war to spread it, didn’t they? Sacred cows were being slaughtered in front of my eyes.

The food arrived. Blini.

“The concept of one or two people attempting to create their own country, usually it never gets beyond those one or two people,” I said. “Why do you think Liberland is so much more successful?”

He considered it between mouthfuls of his borscht, a typical Eastern European soup. “A lot of people believe in the ideals of Liberland. Any nation is only as strong as the people who believe in it. When I was arrested for going there, the chief of the Croatian police came to the court to argue for a longer sentence for me. He said, ‘Liberland is just in your head. It’s just an imagination.’”

Vit laughed, as did his (not-listening) minders. “I told him, ‘Croatia is also just in your head. It’s just an imagination.’ That really pissed him off, of course. But that’s the reality.”

Croatia—imaginary or not—has armies and courts and jails that could be used to convince the doubtful of its existence. Vit has a flag, a website, and a lot of emails from interested people. It didn’t seem like a fair fight.

“Maybe it won’t work.” He shrugged. “Who knows? All we ask is that they let us try it.”

My chance to visit Liberland came a few months later, in 2016, during the country’s first anniversary held near Osijek, Croatia. In the hotel’s car park, a bombshell had just been dropped: President Vit wasn’t coming. Damir, the organiser, was frantic. “They stopped him at the Croatian border! Which is obviously illegal since he’s an EU citizen.”

Inside, the buffet was underway. I got a plate of food and approached a table with one empty seat. “Can I sit here?” I asked. The two men already seated swapped a look, then laughed. “This is Liberland,” one said. “Just take it.”

I took it, put my plate down, and headed to the bar to get a beer. When I returned, someone had taken the chair from me. He’d simply moved my plate of food into the middle of the table and sat himself down. Was this what it would be like in Liberland? Dog eat dog? The person didn’t apologise, so I was left to awkwardly lean over him, pick up my plate, and move to another table.

At the next one, I asked if I could take its empty seat. “No, our friend is going to sit there,” said a man in a flannel lumberjack’s shirt.

Diplomacy was getting me nowhere. I needed to take a page out of President Vit’s book and just put down a flag and declare any seat the Free Republic of Adam’s Ass. The people at the third table did let me join. I found them the middle of an impassioned conversation about gun rights, the main thrust of the argument being that there weren’t enough. A two-man keyboard-and-acoustic-guitar band began playing classic rock covers at the other end of the hall, beginning by strangling and then setting fire to “Don’t worry, Be Happy.”

I turned to talk to a computer programmer from London. “How are you enjoying the conference so far?” I asked him. “It’s very low key,” he said. “No one’s even been arrested yet.”

A few table away an loud, obnoxious man with floppy hair was flirting outrageously with a pretty Turkish woman eating birthday cake as they discussing a private social network for rich people.

“My mother had money, so what, doesn’t matter. I don’t care about money.” He said, balancing his chair precariously on its two rear legs. “I want to be with quality people. Come on, let’s go sailing? You know? No big deal.”

It obviously was a big deal. The woman looked bored. He ploughed on regardless. “Sometimes you eat tuna, sometimes caviar. You know?”

She smiled politely.

“Relax,” he continued. “It’s a joke anyway, right? Who cares?” The girl didn’t appear to care.

He cared. He cared a lot. “Envy, whatever,” he continued. “It’s been a big factor in my life. Probably in yours too. I don’t care about other people.”

She put down her fork. “Me neither. They can talk behind me, I don’t care.”

“I like you, you know,” he said, reaching for her arm. “You’re really great.”

She pulled her hand back. “I’m going outside to smoke a cigarette.”

“Yes, let’s go,” he said, jumping up enthusiastically after her, his chair crashing to the floor behind him.

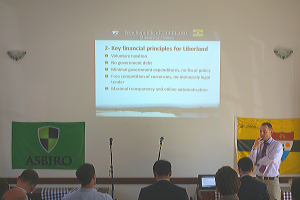

The next day the conference began. I tried to throw off my social-democratic shackles and frolic with this new world view—libertarianism. I found it much less taxing.

As we pulled into the car park of the conference hotel, we found a Croatian police car and two men in suit jackets (wearing plastic earpieces that disappeared into their collars) flanking the building’s entrance.

“Croatian secret police,” said Damir. “Here to try and intimidate us.”

We took our seats inside. “I will now give the floor to Mr President, the founding father and president of Liberland,” said our host, only an hour later than the advertised start time. Above us, on the wall, the face of President Vit Jedlička appeared. “Hell—ooo,” it said. The video froze. “Ev—vvvvv—errry—one.” The sound dropped out, came back, dropped out. “I’m ve—rrrrry happy to seeeeee—”

“Please everyone disconnect from the Wi-Fi. We need the bandwidth for Mr President,” said the stressed-out moderator. A whole country? Seriously? From scratch? These people?

Sure, this was rural Croatia’s fault, not Liberland’s, but rural Croatia had a twenty-five-year head start over Liberland, and look how rubbish it was at providing simple services such as Internet connections speedy enough for Skype. Once the conference did get going, the content was extremely interesting, despite its shabby and chaotic wrapping. We learned more about the area, and why the local government had such a problem with Liberland. We heard from a Croatian politician who summarised it well: “My grandmother has never moved and yet has lived in five or six different countries. It’s no surprise people fear change around here.”

Between conference sessions, we mingled on the large sun terrace. It was surprising how many of the hundred attendees were in suits and had given themselves fancy-sounding bureaucratic titles. They dispensed business cards to each other as children might stickers. For a group who wanted to overthrow the system, they were dressed and behaving remarkably like that system. Which made me wonder if they truly did want to overthrow it or just recreate it somewhere new where they could have its power and make its rules.

A large, fluffy white dog had been sloping about the terrace and sidled up to the gun-loving Brit from the previous night’s dinner. It jumped up and latched on to the man’s leg, which he began humping furiously. The man knocked him down and tried to walk away, but the dog chased him across the terrace. People laughed and cheered. This would have been a funny scene anywhere, but at a libertarian’s conference it was somehow more comical, as if the dog had got caught up in the spirit of the event and was indulging his own sexual liberty. I’d heard the word freedom so many times that day, and this was a very visual reminder how much one person’s freedom can impinge on someone else’s.

The conference was good, but the conference was talk. We wanted action. We wanted to go to the promised land. To squelch our feet in its soggy soil. To be bitten by its libertarian mosquitoes. To tell people we’d visited a country that they hadn’t, a country so new they didn’t even know it (sort of) existed.

The conference was good, but the conference was talk. We wanted action. We wanted to go to the promised land. To squelch our feet in its soggy soil. To be bitten by its libertarian mosquitoes. To tell people we’d visited a country that they hadn’t, a country so new they didn’t even know it (sort of) existed.

And so we climbed into a silver double-decker bus and headed for the Croatian border. We were going to Liberland!

“Borders remind us that we’re all slaves,” said Susanne Tarkowski Tempelhof, the conference’s keynote speaker and creator of something called Bitnation, a tool to replace governments with the blockchain technology used by Bitcoin.

“Yeah. This will all come crashing down soon enough,” said the gun-loving Brit who’d had the romantic encounter with the large white dog.

“Right, because the state doesn’t exist. It’s a collective fiction,” said Susanne’s husband. I looked out at the barriers, security fencing, barbed wire, and people with guns. It looked both very secure and stubbornly non-fictional to me.

All the concerns we’d had about leaving Croatia’s collective fiction proved unfounded. We were waved through their border with a minimum of fuss. They were probably happy to get rid of us. On the other side of it, an affable border guard from the collective fiction known as Serbia got on and collected up our passports. He was a squat man with a small blond moustache. “Where are you going?” he asked.

“We’re going to the other side of the water, to the restaurant,” answered Paul, an English journalist now living in Croatia.

“Oh, it’s very nice,” the official replied. “They have a new chef. His name is Vitrovich. He’s very good. Well, enjoy,” he said, leaving the bus.

Wait, were we all still slaves?

After a quick lunch, and the arrival of Mr President himself, the big moment had arrived: it was time for our voyage to Liberland. We’d all come to the Serbian side to make our attempt so that Vit could join us, being as he was now barred from Croatia. Would we make it onto Liberlandian soil? No one had set foot on Liberland without getting arrested for months.

Our small boat was driven by a calm Austrian called Anton. The engine spluttered into life, filling the boat with diesel fumes. I watched his wild hair blow in the breeze, distracted us from the fact that we had only three life jackets. There was a palpable excitement. The only things that could have made it better were eyepatches, a parrot, and, maybe, a few more life jackets.

Our small boat was driven by a calm Austrian called Anton. The engine spluttered into life, filling the boat with diesel fumes. I watched his wild hair blow in the breeze, distracted us from the fact that we had only three life jackets. There was a palpable excitement. The only things that could have made it better were eyepatches, a parrot, and, maybe, a few more life jackets.

Sat next to me was a shabby, dreadlocked Czech man called Štefan. His T-shirt had a large hole under the armpit. He set about rigging the bright-yellow Liberland flag to a stick, which he tethered to the back of the boat. Once he’d finished, we cheered. We meant business: deregulated business. Since he looked the subversive type, I asked him if he’d ever tried to found his own country.

“No,” he said, a mad glint in his eye. “I did help create a church once, though.”

Of course you did, Štefan. Nothing surprised me with these people. They were doers. They had life by the balls.

“It was called the Cannabis Church. I was a shaman. We were small, but we had a lot of believers.” He mimicked the smoking of an imaginary spliff. “Not just believers. Practising believers. Very devout they were.” He winked. “I’m also planning to create a Procrastination Party. I just didn’t quite get around to it yet.”

About twenty-five minutes into our journey upriver, our yellow Liberland flag flapping triumphantly in the breeze, we found a Croatian police border-patrol boat waiting for us.

“Damn,” said Anton. “I guess they won’t let us pass.”

He accelerated towards them anyway.

“Let’s wave to them,” said the Turkish girl who was obviously still high on birthday cake. We waved at them. We smiled at them. We tried to will these sad vestiges of the broken nationalist system to let us pass on to the shores of Liberland.

The two Croatian policemen did not wave back.

“The system has made their hearts cold,” said Štefan.

Their boats and cold, dead hearts drew closer to us, at speed, creating waves that rocked our little, pitiful sea vessel.

“They’re not trying to tip us over, are they?”

“They wouldn’t dare,” said the future ambassador to Liechtenstein. I think exaggerating his present importance.

Anton surveyed the scene. Inhaled. Steered us closer to them. “Maybe…” he said. I did feel like a slave in this moment.

Their boat stayed in line with ours, on our right-hand side, stopping us from turning and getting any closer to the shores of Liberland, flanking us all the way up the river. We stared at them, they stared back. They were much better at it being professional intimidation operatives of the military industrial complex. They also had uniforms, guns, and a real boat, which helped immensely. By comparison, we were a ramshackle group of hedonists, libertarians, cannabis shaman, and a bald writer. We were equipped for anarcho-capitalism, not confrontation. Unless that was the same thing. I still wasn’t quite sure.

“Oh, come on,” the Turkish girl said. “Let us pass.”

“Can you see that no-mooring sign?” Anton asked. We squinted. Ah, there it was—a small white-and-red sign, possibly hand-painted, some hundred metres ahead.

“That’s the start of Liberland,” he said, proudly.

As borders went it was inauspicious. Anton narrowed the gap between us and the police boat to just two metres. We passed parallel to the sign, our path to shore still blocked. But we’d reached Liberland, sort of. Were alongside it, looking at it, round the edges of a police boat. As promised, it was full of trees, marshland, and mosquitoes, but also had a handsome three-hundred-and-fifty-metre-long white-sand beach front.

“I’m going to open a cafe there,” said Štefan, pointing towards the beach.

“The good kind of cafe, right?” asked the Turkish girl. Štefan didn’t need to answer; the man was a cannabis shaman. After the island, Liberland continued for another hundred metres along the shoreline that Serbia said was probably Croatian, Croatia said was definitely Croatian, President Vit said was Liberland, and I said was handsome. Then, just as subtly as it had started, it ended. We were still thirty metres from the Liberland shore, still being blocked by the police boat. Unable to get any closer to the promised land without getting rammed by a boat, wet, arrested, and having to endure a few days in a Croatian jail, we turned around and headed back.

At the shore, President Vit was waiting. “How do you like Liberland?” he asked. “It’s very beautiful,” I answered, and at that moment, as an idea, and a barren patch of land, it was…

At the shore, President Vit was waiting. “How do you like Liberland?” he asked. “It’s very beautiful,” I answered, and at that moment, as an idea, and a barren patch of land, it was…

It’s certainly easy to dismiss the whole Liberland project as ridiculous. I know I did at the beginning, and during the middle. In fact, I’m not sure I’m totally free of ridicule for it now, at the end of my weekend in its inner circle. Yet the romance of it has me smitten. Every country that now exists began in just the same way as Liberland, with a group of radicals chasing something other people said was impossible. Ask the citizens of Rhodesia, Burma, Ceylon, South Sudan, Yugoslavia, or, closer to home, the German Democratic Republic about the sanctity of borders and the longevity of regimes. The libertarians are right—countries really are collective fictions. They’re also right about the potential of new technology to change those fictions, to create better, fairer stories. It’s already happening. Look around next time you’re in a bar or restaurant or on the subway. How many people are checking out of that physical place and into a virtual one, a digital no-man’s land. Physical location is just not as important as it used to be. Long gone are the days where we are damned to grow up, work, find a partner, raise children, and then die within a hundred kilometres of where we are born. As an immigrant, I’ve experienced the benefits of free movement first-hand.

Does that mean Liberland is going to get its voluntary-taxation, anti-government, cannabis-shaman paradise any time soon? I doubt it. The project is in good shape and the brand is well known and attracts more followers with each passing day. Not that this project is exclusively about politics. I think it’s mostly about fun, adventure, rebellion, and spending the short time we have here on this big spinning rock being part of something bigger, chasing down an impossible dream—indulging in the romance of statehood. My little taster of that life convinced me it’s a good one. Superior to the one where you actually get what you wish for, and then have to try to turn a bit of marshland into a society, armed with only the free market’s invisible hand.

The world’s a much more interesting place because of radicals like the people behind the Liberland project. They have imagination and conviction and that’s more than most. I hope they make it, and I can place my feet on the sandy beach of a real Liberland one day.

This article is adapted from a chapter in my Amazon bestselling travel book Don’t Go There: Chernobyl to North Korea—one man’s quest to lose himself and find everyone else in the world’s strangest places. A few names have been changed.

Had fun?

Then this is the book for you, my friend.

Get new travel stories sent to your mailbox. No spam. Ever. Promise.